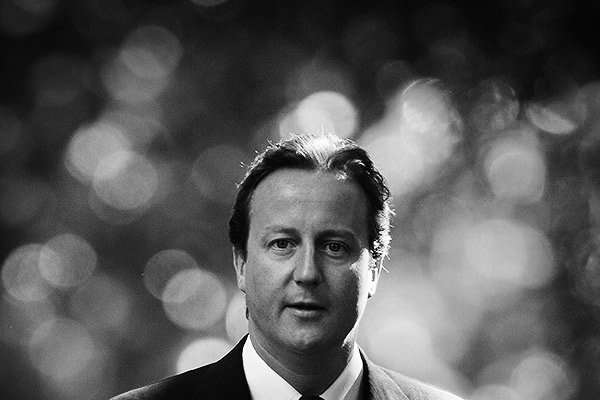

In 2005 the privately much-touted, though previously little-known member for Witney electrified a dour assembly of Conservatives that had recently tasted their third successive general election defeat. Cameron’s parting gift to the assembled delegates was a message that would shortly be communicated, with great success, to the wider electorate. He declared that “a modern compassionate Conservatism is right for our times, right for our party, and right for our country.” In the aftermath of the Referendum, his potential successors share this conviction.

Though historians will debate whether compassionate Conservatism was right for the UK, it is clear that this brand of politics was right for the Tory Party. Two general election victories assured Cameron’s position as the party’s second most successful electioneer in the modern era. Had he not tried to provide a definitive answer to the same question that had brought down the Conservative Party’s greatest vote winner, he may well have equalled her success. And this is an intuition clearly shared by whoever will replace him. Cameron may be gone, but his approach will live on. His successors know that the divisions caused by the referendum result will make compassionate One Nation Conservatism more necessary than ever.

Had Cameron stayed, he was due to unveil a program of opportunity under the umbrella of life chances. Cameron knew that the end-game of compassionate Conservatism was a Conservatism that offered opportunities. He knew that the fruits of globalisation had not been shared, and that sharing them would ensure his legacy. If the European question had been settled to his satisfaction, his government would have rolled out a program that included free school meals, child care for those on the lowest incomes, and comprehensive prison reform.

Since Cameron’s resignation, five conservative politicians have queued up to offer their services, and six have sought to show they have the ointment to soothe an angry, divided nation. All borrowed heavily from Cameron’s ‘life chances’ narrative. Stephen Crabb, a Welshman who grew up in a council estate, promised “a fairer set of opportunities for all”. Michael Gove spoke of giving “everyone a stake in the future”. The frontrunner, Theresa May, offered “a vision of a country that works not for a privileged few but for every one of us”. In a speech where Johnson shocked everyone, nobody will be shocked that he praised “the great reforming legacy” of his rival, before imploring the nation to “invest in our children and improve their life chances”.

However, those jostling for pre-eminence will find that compassionate Conservatism is hard to reconcile with sound economic management- doubly so in a time of disruption. Cameron’s big society initiative didn’t survive contact with the far from propitious economic circumstances of 2010 and the stresses of uniting a divided government. A choice must always be made.

The referendum threw into sharp relief the divisions in the United Kingdom. A prosperous London backed the status quo, while swathes of disillusioned citizens voted to transform the political and economic landscape. In 2005 compassionate Conservatism was the cure for the Conservatives’ electoral malaise. In 2016 the party’s leaders hope it can unite a country. They will find, like their predecessor, that this is far easier said than done.